A much-condensed version of this article can be read here. https://www.francetoday.com/learn/history/berthe-morisot-and-edouard-manet/

In the Parisian art world Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot was a contradiction. Morisot painted under the restrictions she faced as a female artist. However she allowed Manet to exploit her image and character, offsetting the decency she tried so hard to preserve in her own paintings.

|

| Berthe Morisot at her easel painted by her sister Edma wikimedia commons. |

As a member of the Parisian bourgeoisie in the late nineteenth century, painter Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) risked being a woman whose image was harmfully exposed. She was obsessed with Édouard Manet, (1832-1883) and he in turn exploited her. Manet painted more portraits of Morisot than any other model. Capitalizing on their relationship and her willingness, he posed her in ways unconventional for upper class Parisian women. This can be seen in the series of eleven portraits Manet painted of Morisot between 1868 and 1874, in which he captured her in a variety of candid poses. The opposite is observed in the domestic portraits Berthe Morisot produced where the double standard for male and female artists was apparent. The standard for female painters dictated that women should paint only domestic scenes featuring family members and close friends. This was a rule that Morisot adhered to in her work.

Morisot’s correspondence reveals that she had a girlish infatuation

with Édouard Manet. He could have used her as a willing model and lover but

because they were allied by their social position he amended his approach and

sought a compromise. Manet strived to ensure that she legitimized her good name

by marrying his brother Eugène.

|

| Henri Fantin-Latour, 1864, Detail of Homage to Delacroix Musee d'Orsay - photo Hazel Smith |

It was easy to see why Morisot may have been infatuated with Manet. Handsome and gregarious, Édouard Manet was the personification of

charm. Besides his collection of astonishing cravats and the buttery yellow gloves he was frequently depicted wearing, he was in possession of a bold streak of independence that made him a

natural leader. Manet grew up as a gentleman in the aristocratic neighbourhood of Faubourg Saint-Germain

as the son of a judge. Disenchanted by

law school and the navy Manet trained to be an artist. Although he

never considered himself an Impressionist or exhibited with them, Manet could

be considered the godfather of Impressionism. He was infamous for exhibiting controversial

paintings

Berthe Morisot’s positive reputation preceded her. Morisot’s mother heard the second-hand news that when Édouard Manet heard that Henri Fantin-Latour thought Berthe Morisot was rather beautiful "he told him he should have proposed to you.” A year later Manet and Morisot were introduced by Fantin-Latour at the Louvre in the summer of 1868. Morisot wanted to meet Manet for some time; she greatly admired his work for its freedom and sincerity. The Manets and Morisots formed close ties, meeting weekly. These ties resulted in the flirtatious dialogue between the two artists and a productive artistic liaison lasting until the marriage of Berthe Morisot to Eugène Manet in December of 1874.

|

| Edouard Manet, The Balcony 1868 Musee d'Orsay. Photo Hazel Smith |

Fantin-Latour was attracted to Berthe Morisot and so was Manet. By the autumn of 1868 Manet had convinced Morisot to pose for The Balcony. Both must have realized the risk she was taking by posing for such a controversial artist. As a model, Morisot would be exposed to criticism and rumour. She was Manet’s replacement for model Victorine Meurent which could have ruined her reputation.

|

| Victorine Meurent in a detail from Manet;s 1863 Dejeuner Sur l'Herbe - Musee d'Orsay. The green is for effect only. Photo by Hazel Smith |

Meurent, was perhaps incorrectly considered a woman of the streets who modeled for Manet's famous works. The abuse the Victorine Meuent had to face was considerable. As the model for Dejeuner Sur l'herbe (1863) and exhibited at the Salon of the same year and Olympia exhibited two years following, the figure of Meurent was described as, "a female gorilla," "a coal-lady from the Bagtignolle," " a red-head of of perfect ugliness," " a corpse-displayed in the morgue." However by 1868 Victorine seems to have vanished - she had not been heard from for 3 years. Morisot was to become Manet's favourite model

The Balcony was exhibited at the Salon of 1869. Behind a railing of verdigris

and contained within the shutters of a window, Manet assembled four figures all

looking in different directions. Fanny Claus, Antoine Guillemet

and Leon Koella, stand behind the seated Morisot as she looks intently off the

balcony. Berthe is dressed

in a voluminous virginal white gown and wears large Spanish-inspired jewelry. The

work was influenced by Goya’s Majas on a

Balcony (c. 1800-1810) and possibly Manet’s youthful trip to

The spectre of the Paris Salon of 1869 made Manet nervous as attacks

on his works had become an annual ritual. As Manet’s model Morisot seems to

have been saved most of the ridicule . In this case, she seems to be

her own biggest critic. “I am more strange than ugly.” Berthe wrote to her

sister after the opening day of the 1869 Salon., “It seems that the epithet of

femme fatale has been circulating among the curious.”

As a model Morisot brought Manet good fortune. Berthe corresponded

with her sister Edma. “poor Manet, he is sad; his exhibition, as usual, does

not appeal to the public, which is for him always a source of wonder.

Nevertheless, he had said that I had brought him luck and he had had an offer for Le Balcon.” Berthe’s mother wrote to

Edma on May 23, 1869 about the sad Manet with a brave face. “…his lack of

success saddens him…he meets people who avoid him in order not to have to talk

about his painting, and as a result no longer has the courage to ask anyone to

pose for him.”

Luckily for Manet Morisot agreed to serve as a model for further

works including The Repose (1870) and

Berthe Morisot and a Bouquet of Violets

(1872). Representations of Morisot outnumbered Manet’s representations of

Victorine Meurent, making Morisot one of the most visible models of the 1860s

and 1870s. Although always properly clothed

she still had to put up with contempt and mockery when his portraits of her

were shown at the Salon. Manet risked his new friend’s character to further his

career. He jeopardized her reputation as a respectable young spinster. On

display, she was a commodity to be ogled, criticized and ultimately bought.

From her own experience Morisot knew instinctively that women had to be shuttered off from public view and protected. As a nineteenth century female artist, she worked from a different point of view than her male colleagues where discriminatory restraints closed a range of places and subjects to her . The private areas and domestic spaces that female artists could represent at this time included dining rooms, drawing rooms, bedrooms, balconies, verandas and private gardens.

Bars, cafes and the backstage were off limits to respectable women let alone respectable female artists. Victorine Meurent, and Suzanne Valadon who would follow, were unlike the almost upper-class Morisot girls, their lower class upbringings gave them carte-blanche to go hither and yon.

Morisot was left to paint the members of her family circle. For bourgeois women, mingling with mixed metropolitan crowds was frightening because it was unfamiliar and morally dangerous. For example, at the Salon of 1869, where The Balcony was introduced Morisot did not think it appropriate for her to walk around unaccompanied. After losing sight of Manet at the show she said, “I did not think it proper to walk around all alone. When I finally found Manet, I reproached him for his behavior; he answered that I could count on his devotion, but nevertheless he would never risk playing the part of a child’s nurse.”

The women Manet was able to paint represented mistresses, courtesans

such as Nana in her boudoir (1877) and working class women often suspected of covertly

working as prostitutes, as is the model in the Bar at the Folies Bergere (1882). Berthe Morisot would have been well-aware that her

predecessor Victorine Meurent represented these types in

More boundaries are observed in Morisot’s paintings. Her arrangements often consisted of spatial compartments . The women in Morisot’s paintings are often bounded within a tight confining space or separated from the scene by a veranda or balustrade or balcony. Her spaces restrict and at the same time, shelter her subjects. With her domestic, feminine subjects Morisot worked like a natural scientist, revealing the specimen of upper class women and examining their social life, furnishing and interiors as one would a caged bird or pinned butterfly. The Artist’s Sister at the Window (1869-70) shows Berthe Morisot’s sister Edma in a window similar to the one that Morisot poses in for Manet’s Balcony but Edma is seated indoors, essentially caged inside the window and balcony from the world beyond. Edma is hatless and is dressed white. She absent-mindedly fondles a fan; more intent on her internal thoughts than the scene on the street, whereas Morisot was depicted by Manet as intently observing the passing scene from the balcony.

|

| Berthe Morisot - The Artist's Sister at a Window, 1869. National Gallery of Art Washington via Wikimedia. |

Here Morisot’s balcony demarcates the interior, private lives of women versus the external public sphere of men. In this painting, Edma Pontillon née Morisot, was at the Morisot family home in the winter of 1869-1870 for her confinement during the last stages of her pregnancy. She’s defined by this feminine non-social space of sentiment and motherhood from which the worries of money and power were banished.

(Please read on to Part 2 of MMM)

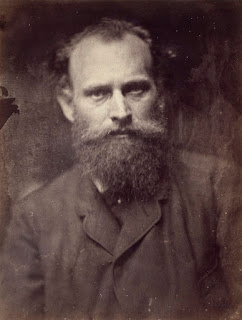

top photos: Berthe Morisot - Unknown photographer. Image Via Wikipedia

Edouard Manet by David Wilkie Wynfield. Royal Academy of Arts. Royal Academy.org. uk

Works Cited

Armstrong,

Carol M. Manet Manette.

Friedrich,

Otto.

Gedo, Mary

M. Psychoanalytic Perspectives on

Art: PPA, Volume 2. Hillsdale, N.J: Analytic Press, 1985. .

Harrison,

Charles, Paul Wood, and Jason Gaiger. Art

in Theory, 1815-1900: An Anthology of Changing Ideas.

Herbert,

Robert L. Impressionism: Art, Leisure and

Parisian Society.

King,

Ross. The Judgement of

Locke,

Manet, Julie,

Rosalind B. Roberts, and Jane Roberts. Growing

Up with the Impressionists: The Diary of Julie Manet.

Morisot,

Berthe, and Denis Rouart. Berthe

Morisot, The Correspondence.

Pollock,

Griselda. Vision and Difference:

Feminism, Femininity and the Histories of Art.

Rubin, James H. Impressionism.

Comments

Post a Comment